Photo credit – Tim Bowditch

Ipek Duben: In via incognita

Gemma Padley

Pi Artworks

55 Eastcastle Street, London, W1W 8EG

01.03.18 - 07.04.18

Stepping inside Pi Artworks’s latest solo exhibition featuring the work of Turkish multimedia artist Ipek Duben is a strange and disconcerting, troubling, even, experience. As you leave behind the hustle and bustle of London’s Fitzrovia, Duben transports the viewer into a world of silent screams and desperate realities where unrealised hopes and stolen dreams abound.

In via incognita, (which loosely translates as ‘unknown path’) is Duben’s first major show of works in London since the early 1980s. It takes global migration as its central theme, a pressing issue not only of our time, but, as Duben’s powerful exhibition reminds us, one that has been part of the fabric of human existence for decades.

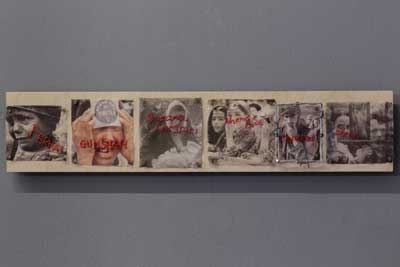

Take the 12.5 metre long display (of the same name as the exhibition) that stretches across two of the gallery’s walls, for example. Among the sadly all too familiar newspaper images of migrants and refugees in precarious looking boats are photographs dating back to the early 20th century – to the Balkan War of 1912. Printed on fragile pieces of tulle fabric, each frame has a barbed wire border to symbolise, we assume, the physical and mental imprisonment and trauma global migrants have endured for years and endure still. The individual frames, like windows onto history through which we glimpse displaced people from all over the world, unapologetically command our attention.

As a whole, this work, akin to a filmstrip, offers a striking cinematic view that weaves a thought-provoking and disturbing narrative about the treatment and experiences of migrants throughout history. It’s a powerful piece and difficult to tear your eyes away from, but while Duben alludes to moments in history and specific territories – the people depicted come from all over the world including India, Mexico, Gaza, Rwanda, Armenia, Afghanistan and more – where they are from and when they lived is less important than a key message the work conveys simply but convincingly: that recent refugee crises are nothing new – there has always been migration of some kind, and tragically, human suffering has always gone along with it.

That this suffering has happened and continues to happen doesn’t make it OK of course, but Duben forces us sit up and take notice. You never get the sense, however, that she is hammering home an overtly political message. Duben’s approach feels quieter, more nuanced and observational, but is all the more effective for it.

Her Untitled Portraits (2017) series featuring small silk-screen prints of portraits of refugees with their names hand crocheted across them by the artist – the human faces of migration – also draws the eye, but the projection Farewell My Homeland, an older work (from 2004) in which snippets of text adapted from newspaper articles and interviews by Duben are shown on a loop, was the work I spent the most time with. In this sobering piece words tumble poignantly down the wall and are presented in such a way as to read almost like poetry. ‘I once owned a house. I had a table where my children and I could eat. We were human beings then,’ reads one excerpt. Each fragment of text cuts to the quick. An installation in front the projection includes a book of images printed onto synthetic silk. The book is encased in chicken wire rendering it untouchable and unreadable – another metaphor for migration and the notion of being trapped, perhaps.

In via incognita, far from easy viewing, demands that visitors look closely at what’s being presented and immerse themselves in the worlds on display. What we get is a pertinent and damning, but necessary, critique of humanity.