Photo credit - Cemil Akgül

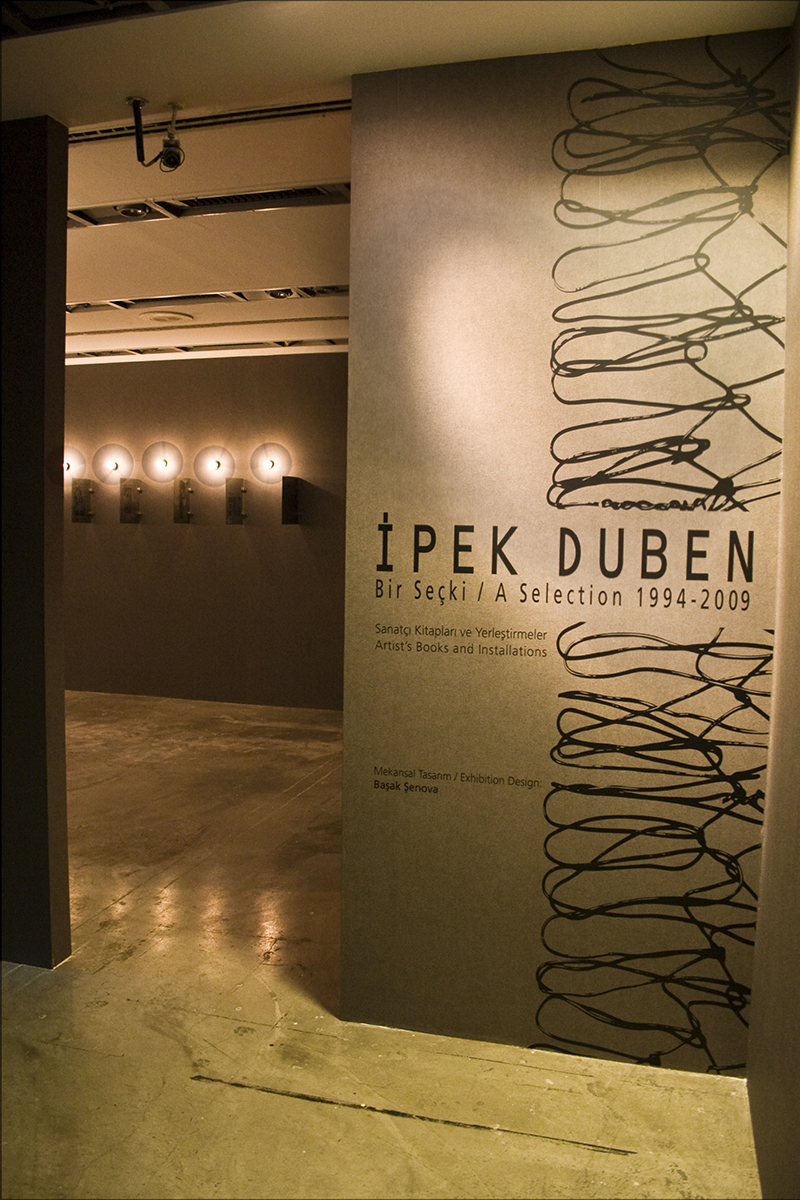

İpek Duben a Selection: 1994-2009

Robert Morgan

Excerpts from exhibition catalog

İpek Duben:

Bir Seçki/A Selection 1994-2009

, Akbank Sanat, 2009

In reflecting on İpek Duben’s work, I do so from the perspective of a New York critic who travels several times a year to other parts of the world. I am not sure whether this gives me an advantage or disadvantage in terms of how I judge what I see. Some are of the opinion that the concept of art is rapidly changing, corresponding, perhaps, to the changes emanating from digital communication technologies. As a result, there is a tendency for some critics to run faster in order to catch up with everything “new” in art, often failing to see what is truly significant. But my understanding of the critic’s role is different from this. Rather than speeding up, one should compensate for all the mediocre excess by learning to slow down. There is a certain virtue to seeing things from a distance, and allowing art to take its time in relation to the process of reflection.

In the case of İpek Duben, I read her work as a kind of visual poetry that employs both feminist and cultural activism, replete with psychological and political messages. Her interdisciplinary approach to art is expressed through mixed media that includes photomechanical processes, assemblage, written poetry, artist’s books, installation, and filmmaking. One might argue that Duben’s project as an artist is a phenomenon that begins from the center and gradually moves outward. Or perhaps the more appropriate metaphor would be a sliding glissando, where tones move from one register to another, from low to high, and high to low. Regardless of its direction, her art depends on an ability to function in relation to perpetual change. She is less concerned with what is “new” than with what is perpetually shifting away from the expectations that we give to art. In any case, Duben’s multicultural reference points reveal a steady course that explores nuances of emotion, portraiture, and intellectual peregrinations in relation to the external world of secular events.

Significant artists emerge from vastly diverse cultures and often from highly divergent political contexts. There is no special quarter, no special geography, no special race, gender, age, or ethnic origin, where this phenomenon is likely to occur. Some inner-directed artists, like Duben, exist nomadically at all times and in various places. This reality has taken a new position in art as travel and communications have become more accessible in recent years.

Duben functions as an artist with a nomadic instinct. Given the range of her experience and intellect, I believe Duben has emerged as an important trans-cultural artist, not just a Turkish one. She is an artist motivated to tell the truth through subjective memory, perception, and insight about the fate of a woman born into the culture of the Middle East who discovers intimate forms of expression that become universal. Like the late French novelist and playwright Jean Genet or the ineluctable feminist philosopher and novelist, Simone de Beauvoir, if one goes deeply enough within oneself, the results become universal. To reach a platitude of significance in one’s work is less a matter of reaching for external signs, than retrieving those signs within the experiential torrents of oneself, and sublimating these conflicts into original forms that transmit meaning beyond all predictions or expectations.

In this sense, İpek Duben has maintained a consistent aesthetic rhythm throughout her career—a position that makes her a universal artist. She has entered into a transcultural world both as a feminist and as a Turk. She advocates fundamental values that are not only the concerns of women, but also the concerns of those who aspire to making a more just, fair, and humane environment. Yet Duben is not an ideologue bent on repeating the same rhetoric in multiple forms. A quintessential humanist, Duben searches for the structure of common values that serve the cause of signifying a better world. Her raw material always begins with her own experience and the transformation of experiences into forms that communicate beyond the boundaries of race, ethnicity, political groups, or nation states. While she is consistent in questioning the blindness of power, she is also compassionate in exposing the countless refugees and emigrants victimized and brutalized by those who aspire to power. This is evidenced in Farewellmyhomeland, consisting of an artist’s book (2004) and a major installation and film document (2007), shown at the Munson-Williams-Proctor Museum in Utica, New York. Given that Duben’s propensity is to function as a total artist—what some might call a “conceptual artist”—her message is both lucid and relentless, persuasive and direct, challenging and elegant, regardless of what medium or combination of media she chooses to employ.

While Duben trained as an artist both in the United States and Turkey, the thematic structure of her mature work did not begin to evolve until the early nineties. A decade earlier, she was still focused on figurative painting and sculpture, and occasionally on self-portraiture. Upon her return to Istanbul in the late seventies after studying art for several years in New York she soon discovered that “modeling was not an easily acceptable or desirable occupation or experience for most people.” One of Duben’s first encounters in trying to paint a model came when she asked a woman, named Şerife, an Anatolian immigrant working as a house cleaner in Istanbul, if she would pose in the artist’s studio. The woman refused. Finally she allowed Duben to photograph her fully clothed but without showing her face. Duben recalls making a dummy by filling out Şerife’s dress with crushed newspapers and pinning it to the wall to paint as though it were a live model: “Her absence was her signature. I felt that I had painted the iconographic Turkish woman.”

After completing a dissertation on Turkish Painting and Criticism: 1880–1945 (1984) at Mimar Sinan University, Duben returned to studio practice with the ironic Muscle Man series (1988). The decisive turn came with Traces (1991)—ten large paintings on vellum and canvas—where she brought together content drawn from Mongolian and Persian miniatures with vigorous gestural forms informed by the Abstract Expressionists. Courageously exploring sources beyond her indigenous tradition, Duben began to transform meaning within her own culture, pursuing a cultural feminism and an invented symbolic language capable of challenging former interpretations.

Traces was shown at Maçka Art Gallery in 1991, accompanied by a panel on feminism and multiculturalism. A related mixed-media work, Register, followed, leading to Duben’s first artist’s book and multimedia installation, Manuscript 1994. Although she has referred to it as “an autobiographical statement,” the work’s conceptual system—portraits and densely painted panels arranged in rows, a vitrine-like table displaying a cover resembling the Qur’an, and a closing bilingual poem—extends beyond the personal to a broader, formally complete undertaking.

Duben’s self-taxonomy charts two early tracks—feminist consciousness (e.g., Şerife, Muscle Man) and cultural synthesis (Traces, Register)—which culminate in Manuscript 1994. The next phase moves toward political and social criticism: borders between nation states (News from the West, 1997), cultural identity (What is a Turk?, 2003), forced immigration (Farewell My Homeland, 2004/2007), and mass-media anonymity in intimate life (LoveBook/LoveGame, 2001). In addressing these concerns, Duben speaks in multimedia, joining a global feminist vanguard.

Farewell My Homeland (2004) prints refugee images on synthetic silk, bound with wire chain-link covers and housed in a wooden valise—portable across borders. The work became an installation in 2007 (Borusan; Munson-Williams-Proctor). In Crossing (2007), Duben hand-embroiders names, dates, and places, confronting “robotic textiles” with the artist’s touch. In What is a Turk? (2003), she mailed thirty postcards to Istanbul residents from varied backgrounds, gathering impressions that challenge inherited stereotypes. Earlier, in News from the West (1997), a valise traveled between Vienna and Istanbul with works secretly transported across borders, talismaned by a hidden “evil eye”.

The narrative does not end here. Duben’s art is a means to restore memory in a time when proliferating electronic codes and biochemical diffusion work against it. Without memory there is no history; without history there is no art—only simulacra. In the film Thinking Garbage (2005, with Nancy Atakan), Zygmunt Bauman’s “Wasted Lives” undergirds a sequence of fleeting human images reduced to anxious consumers. Saddened, we grasp the message: the world is filling with garbage—yet art remains a reality that confronts disappearance and the beginnings of a lost history.

Robert C. Morgan is an artist, writer, and art critic who teaches in the Graduate Fine Arts program at Pratt Institute. Selected books include Art into Ideas (Cambridge University Press, 1996), The End of the Art World (Allworth, 1998), Bruce Nauman (Johns Hopkins, 2002), Clement Greenberg: Late Writings (University of Minnesota, 2003), and The Artist and Globalization (Municipal Gallery, Łódź, 2008). In 2009 he had solo exhibitions at Bjorn Ressle Gallery, New York, and Sideshow, Brooklyn.