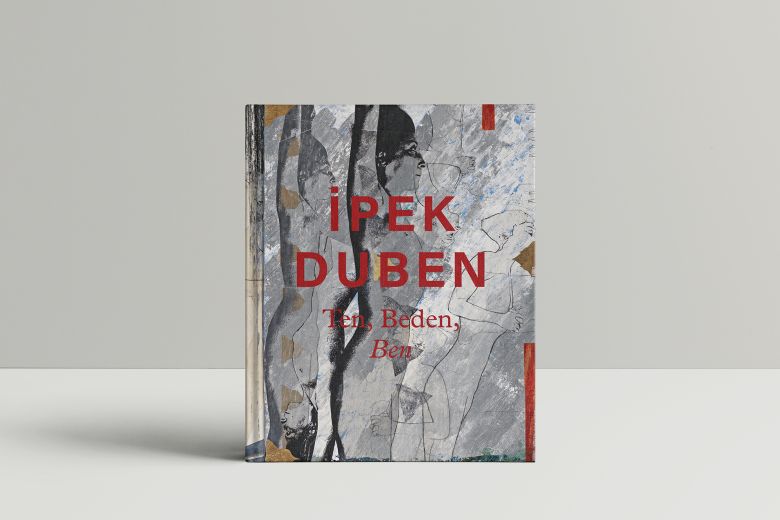

İpek Duben: Ten, Beden, Ben, Salt/Garanti Kültür A.Ş. (Istanbul), Mousse Publishing (Milan), 2024

Design: Esen Karol

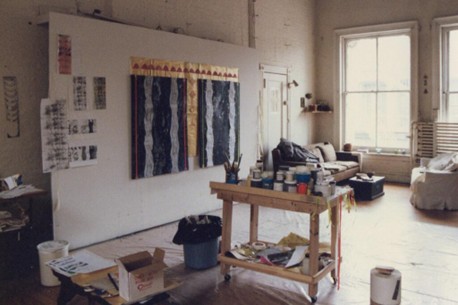

View from İpek Duben's studio, SoHo (New York), 1992

Salt Research, İpek Duben Archive.

İpek Duben at the Manuscript 1994 exhibition, Istanbul Municipality Taksim Art Gallery, 1994

Salt Research, İpek Duben Archive